The Year I Went From Six Figures To Zero - Part One

A wander through a financial history to examine the influence of money on decision making

That’s not a typo.

Talking about money is awkward, isn’t it? We hate talking about how much we have or don’t have, hate being asked for it, and even more, hate asking for it. Just me? Didn’t think so.

Today, I’m going to swallow my discomfort and tell you about my reverse fairytale. I’ve never really been one to fit with trends. So instead of another story about how I went from zero to a six figure salary and here’s-how-you-can-do-it-too (because you can find one of those anywhere), here’s my reality: a story of going from a stable, comfortable, six figure income to zero, and why, for now at least, I am happier than I’ve been in a very long time.

Before you all click away, this is not an article where I am trying to sell anything. I don’t even have anything to sell at this point. All of my essays are free to read, and my intention is that they will stay that way.

I hope that you won’t be terribly disappointed, but this is not a riches to rags tale, nor is it one where I shall proclaim that the joy in this, my creative venture is reward enough that I can live on beans on toast (quite the opposite, in fact - the starving artist stereotype needs to go in the bin, as, frankly, can the baked beans). The point of this (three-part, because it is long) essay is to explore how our relationship with our finances can affect our decisions in ways that are at times counterproductive. Most importantly, I want to break some of the taboos around money that exist to serve only the capitalist patriarchy. So in my usual, over-sharing style, get ready to know more than you ever wanted about the state of my bank account.

And you never know, maybe one day we’ll look back at this as the baseline for my 100k to zero to the next Melinda French Gates/Taylor Swift story.1 Or something.

So, how did I get here?

Rewind one year

For those of you who are meeting me for the first time in this essay (and whether you are or not, thank you for being here!):

Hi, I’m Louise. One year ago, I was a Consultant Paediatric and Neonatal Surgeon at a major UK children’s hospital.

Now? I’m unemployed. If you want to know more about my journey to medicine and my decision to lay down my scalpel, check the footnotes for a link2.

I’m aware that my readership has a diverse background. I hope that those of you who work in the UK health service - so already understand how doctor salaries work - will allow me a little time to explain for the benefit of the international and non-medical readers.

When you think of the job title ‘consultant surgeon’, does that bring any presumption about income, or wealth in general, to mind?

Let’s see how close you were.

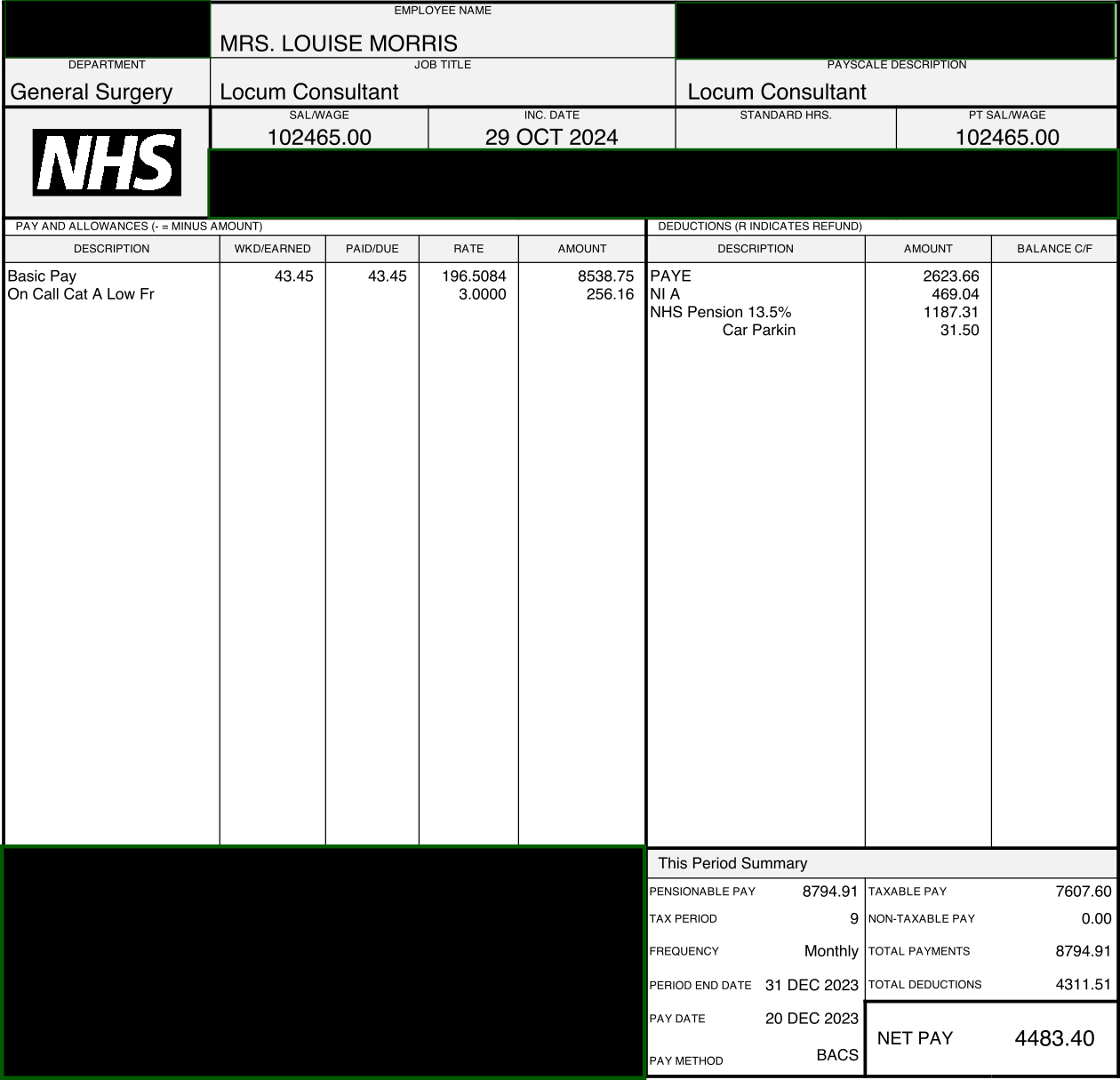

This is my payslip from December 2023:

This time last year, my annual salary in my post as an NHS consultant surgeon was £105,539 ( ~$133k). The basic salary for a 40 hour working week was £102,465 per year, with a 3% supplement for being on call 1:103. Take home monthly pay after taxes, pension contributions, and the fee to park at work (let’s not forget that), was around £4.5k (~$5.6k).

I earned a good salary, nobody would deny that. Whether it’s comparable to the income of surgeons abroad, or whether it’s considered fair recompense for the training, responsibility and work done, are much bigger questions, and not really the point of this essay, so allow me to park them for now.

On 2nd July, 2024 my fixed term contract of employment ended. For the rest of 2024, I earned zero.

Now, that is not the entire story, because as those in the UK may recall, there were a series of NHS strike actions across 2023-24 as a result of an industrial dispute between doctors and the government. When resident doctors were on strike, consultants necessarily ‘stepped down’ to cover their shifts, to maintain safe emergency cover for our patients. Because this work was extra-contractual and largely unattractive to many doctors with a degree of unresolved trauma from our own junior years, we were paid much more than our usual hourly pay, with rates of up to £269 per hour4. My final shifts as a consultant happened to fall during one such strike period. I had volunteered to work the night shifts in the knowledge that, with no active vacancies in my specialty in the UK, I may not have an income for some time. The approximately £13,000 I earned during this set of nights covered the first few months of my mortgage payments in that second half of 2024. Since then, I’ve been using savings to cover the shortfall.

Let’s go back a little further

To understand my own relationship with money, I went on a deep dive through my financial history. To continue in the spirit of openness, here is what I found:

Childhood

Base pay £1 per week (pocket money) | Attitude to money: Collector

I was a saver.

I inherited this from my parents, I think. I have vivid memories of my Mum carefully transcribing the sum from every grocery store receipt into the back of her chequebook. With a natural affinity for numbers and a background of work in a tax office, her meticulous approach to budgeting taught me the importance of financial awareness from a young age.

I was a child who put every tenner from a birthday card in the bank. I liked the idea of being prepared for a ‘rainy day’, but more than that, I was seduced by the thrill of a new line printed in my account deposit book, proudly announcing its slowly but surely rising sum (I don’t think I’d heard of inflation). My coins were saved in a plastic house-shaped money box, a staple of local childhood bedroom windowsills, from the small branch of the (then) Halifax Building Society in our town.

My first job, re-shelving returned books in my sixth-form college library earned me £3.68 per hour. The pride of earning for the first time was enormous. I felt a freedom from that regular income that gave me the confidence to spend, still judiciously, but I was able to ease off on my mentality of saving everything I could ‘for the future’. It made me all warm and fuzzy to be able to buy a round of drinks for my family or a birthday card for a friend. I realised I was happier to spend on gifts for loved ones than on myself, and that still applies. I guess gift-giving is one of my predominant love languages.

University

Base pay ~£2k per semester (loan) | Attitude to money: Cautious

I went to university in 2001. Tuition fees were a new thing in the UK - up until 1998, degree students had received free tuition, and prior to 1990, 100% maintenance grants to support students’ living expenses were the norm. My parents, having assiduously saved throughout the nineties to support mine and my sister’s education, very generously covered my accommodation costs and paid my tuition fees of ~£1,000 per year. I took out the maximum available student loan and took on a job doing admin work in a GP surgery during the holidays, to fund the rest of my living expenses. In terms of my attitude to money back then, I think a good description would be ‘cautious’. I knew that I wouldn’t be going on the much-hyped medics’ ski trips, for example - the costs were prohibitive, and I had no idea how to ski anyway.

Going to university in Nottingham, only an hour from my childhood home in Yorkshire, I was soon feeling the culture shock of living in halls of residence alongside peers with backgrounds of such wealth that we struggled to find any common ground to relate on. There were notable exceptions, thank goodness, and I am fortunate to have met some of my lifelong friends at university. The difference between the haves- and the have-never-heard-of-a-haircut-that-costs-that-much was mind-blowing, though.

I was careful with expenses in my student years. It was a time of cheap clothes and cheap drinks - exemplified in the snapshot above of a 21-year-old me wearing £2.50 worth of fancy dress accessories at a house party where we drank from a plastic tub filled with a neon cocktail of Lambrini, White Lightning and a whole bottle of fruit cordial. Vodka too, for the hardcore (I wasn’t). The one expense I didn’t thrift on, was books. I excitedly shopped for every textbook on the prescribed reading list for my course. Some remain, virtually unused on my bookshelf, now too outdated to be useful even to donate. Story books though, I devoured. I dreamed, lost in fictional lives and worlds where I didn’t have to worry about fitting in.

My ‘life’ savings, if you can call it that at 20 years of age, along with a £1,000 inheritance, paid for my first car in 2003. In my third year of medical school at that point, I was required to travel for placements at hospitals across the region. My aptly named Peugeot 106 Independence model cost £6,200. I kept it for 16 years.

I graduated in 2006 with a student loan of £19,329 and an overdraft of around £1,000. Adjusted for inflation, that approximates to debt of £35k today. Having long abhorred the concept of debt, I was relieved to realise I was able to be conscious of it while accepting it’s existence. I was in a privileged position, in possession of a medical degree and with a first job lined up. The concept of medicine as a ‘job for life’ was touted frequently back then, particularly with an undercurrent of envy from peers graduating with degrees that were more academic than vocational.

In contrast with medical students today, currently facing annual tuition fees of £9,535 from September 2025 and an average student loan liability on graduation exceeding £100k, I entered the workforce with a relative security. Optimistic about the career and life of relative wealth that lay ahead, I was content in my naivety.

Who would have thought that 19 years later, I’d be writing about where it all went wrong?

In part 2, due for release next week, we’ll wander through the junior doctor years on my path to a six-figure salary and explore how my relationship with money has changed now that six has turned to none.

Would you join me?

Louise x

Parts Two and Three were published since this article was first written, they can be found here:

Or whoever your ethical billionaire of choice is - if those two words are not a contradiction in terms given what I said above about the capitalist patriarchy - but tbh right now anyone other than the rich white dudes currently hell bent on ruining the world will do. Actually, I don’t want to be a billionaire at all. They probably shouldn’t exist, but if they have to, let’s have a matriarchy, please!

Articles explaining the story behind my decision to leave medicine can be found here:

Part One

Part Two

A 1:10 rota means that I was one of ten surgeons who took turns to cover the surgical inpatients and emergency referrals between the hours between 5pm and 8am Monday-Friday, and a 24 hour period at a time at weekends. One in ten evenings, nights and weekends I was available to take telephone calls, discuss cases, make decisions, and go in to the hospital any time to see patients and/or perform surgery when required.

£269/hr rate was applicable only between the hours of 11pm and 7am. This link is for the full rate card as recommended by the British Medical Association for the 2023-4 strike periods. Not all hospital trusts paid at this level, though mine did. The BMA withdrew the rate card in 2024 as a condition of the settlement which brought the industrial action to an end, so the document is only currently applicable in Northern Ireland.

You write with a very engaging, accessible style about topics that might be dry or difficult to understand otherwise Louise. Consider me hooked.

I'm looking forward to hearing more. Thank you for writing about this. I too find it difficult to talk about money, so I admire your courage.