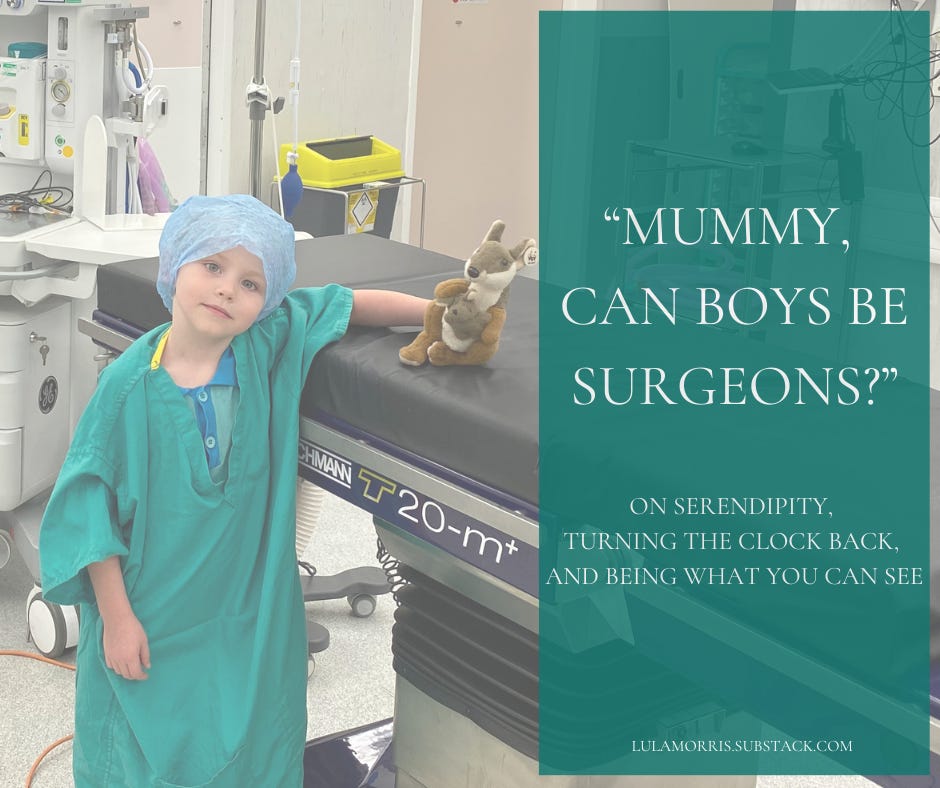

‘Mummy, can boys be surgeons?’

On serendipity, turning the clock back, and being what you can see

‘Maybe… a recycling truck driver?’ My son, around the age of 4 and a big fan of Dr Ranj’s superhero book, was debating what he wanted to be when he grew up. I nodded along, mind elsewhere. ‘Ooooh or a firefighter!’ I added a vague ‘Mmhmm’, not that I wasn’t interested, but this was not the first time we’d had this conversation this week. He went quiet for a moment. Then ‘Mummmmmyyyyyy’, he was building up to a big question here: ‘can boys be surgeons?’.

Obviously, I said no1.

That one got my attention, though. How incredible that the oh so common stereotype of boys-are-doctors-and-girls-are-nurses had completely passed my boy by. His only reference point for what a surgeon looks like, was me. It certainly made me pause and reflect on how important role models can be in giving us permission to not only dream, but believe in what is actually possible. I have to admit, it made me smile quite a lot, too!

Serendipity or design?

I’ve never considered myself a writer before now. I haven’t written for pleasure, well, ever really. But something made me click on to

’s Winter Writing Sanctuary course when a social media algorithm aligned with my scrolling finger, and from that one click a snowball set off tumbling down a remote mountain, and my work, and life, is now taking on a whole new direction. One tiny decision, followed by a series of further tiny decisions - to actually sign up for the course; to try out day one; to keep going; collectively leading to this new focus, and with it: joy. I think a big part of my persistence, this ability to keep going, has come from Beth herself. As a role model: a woman living a successful, creative, joyful life, doing what she loves, there is a lot to be inspired by. She teaches that if we write, we are writers, and the world needs our words. All I have to do then, is find my voice. (Incidentally this applies both literally and metaphorically at the moment, having entirely lost my actual voice to a bout of laryngitis).In writing, and working out what I want to write about, I’m learning a lot about myself, how I want to show up in the world, and what is really important. There’s a deep layer of creativity here to be explored, and that’s an exciting place to be. It’s interesting then, as I negotiate this career-crossroads, to look back at how role models have played such a big part in my decisions up to this point.

As I’ve written about previously, I decided I wanted to be a doctor at a very young age. My first role model was Dr S - a wonderful, kind GP who invited me to sit in on her surgery and spoke realistically about the career I was so keen to enter. She gave me my first stethoscope as a gift when I left for university. She even indirectly helped me to pass my medical school interview; when I was asked ‘Why should we give you a place to study here, when men who will not need time off to have children can put more back into the NHS?’ (Yes, I was really asked that!), I replied giving the example of Dr S who had returned to full time work six months after the birth of her twins.2 I think I imagined I might one day work as a GP like her; I certainly never saw myself as a surgeon.

Before medical school, I knew so little about the profession that I don’t think I’d even realised that a medical degree doesn’t actually qualify one for very much at all. Even the shortest path to independent practice requires a minimum of five more years of work-based training. For most surgical specialties, that five becomes ten. Minimum. It was presented as fact by even the most well-meaning surgeons (men) that for those of us bound by the biological facts of womanhood: career and family were not compatible and so a choice to prioritise one over the other would have to be made at some point.

Even through my early years at medical school, unlike the ‘rugby boys’ who talked the talk as if they were already replacing hips and knees at the weekend, or the children-of-surgeons who had grown up to follow in a parent’s (usually Dad, let’s be realistic here) footsteps, the possibility of me becoming a surgeon never entered my mind. Until a placement in my fourth year and an allocation to one particular clinic on one ordinary Monday changed the course of my life.

The reason I’m telling this story today, is that it illustrates perfectly how the direction of our lives can be altered by one chance meeting with one particularly inspiring person, especially if that person is successful in a field that we might not have considered as having space for someone like us, especially if that person looks a lot like the version of ourselves we might hope to become.

You see, you can only be what you can see.

Turning the clock back: children’s outpatient clinic, 2004

‘How are you enjoying your week in paediatric surgery?’ Ms A asked me, as I shuffled my chair to protect my eyes from the afternoon sun streaming through the window-blind, yet still trying to stay out of the way (as a medical student, I was almost always in the way).

‘It’s been really good, thanks!’ I think I was prone to respond overenthusiastically to such questions. The truth was, I hadn’t had the opportunity to see very much, yet. My previous surgical placements had not filled me with any career ambition, and I wasn’t expecting this to be any different.

The clinic that afternoon was a revolving door of tiny babies (cute!), small children with a variety of lumps and bumps, and teenagers taller than both me and the surgeon. They came with parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, and I watched Ms A speak to each child and family member as if they were the only person that mattered to her that day. It was an afternoon of smiles and a masterclass of good practice. In between patients we’d chat about the diagnosis or something else interesting she wanted to teach me. She asked about my studies to date and where I was from. I heard about her own children (two boys) and how she’d fallen in love with this specialty because of the immense satisfaction of working with young patients and the challenge brought by a practice defined more by age than body part. I’d never met a doctor who was so generous with her time and seemed so genuinely interested in what I had to say. I had also never met a surgeon who was both a woman and a mother. In that one afternoon, I think I’d already decided I wanted to be her when I ‘grew up’.

Towards the end of clinic, her phone rang. ‘Ooooh ok’ I heard her say. ‘Do the radiologists know?’ She was looking concerned in a way that I hadn’t seen through reviews of the last twenty patients that had come through the door. ‘Right, thanks, lets hope they arrive soon then!’ She hung up. ‘What are you doing this evening?’ she asked, turning to me. ‘Nothing much.’ I didn’t want to admit that my evening would probably consist of watching Neighbours then eating a bowl of chips and cheese before getting an early night. ‘Well then’ she looked enthused, ‘there’s a baby coming over from Lincolnshire with green vomiting. I’m on call tonight; why don’t you stay? We can go and see them and you can watch the scan, it’ll be interesting!’ So enthralled by her energy was I, I think I’d have followed her anywhere. I was mindful though that two of my cohort of students were allocated for on call that day, so I shouldn’t step on their toes. As it happened, they’d already lost interest and gone home at 3pm, so who was I to deny the universe’s alignment?!

At this point in my studies, I knew little about vomiting in babies, or anyone, for that matter. What I did know, was that it shouldn’t be green. I remembered from my anatomy classes that intestinal contents are only green when mixed with bile, the thick liquid produced in the liver and released by the gallbladder after a meal. The duct from the gallbladder enters the intestine in the duodenum - the first part of the small intestine. While ‘normal’ vomiting would just bring up stomach contents (not green), green vomit usually meant there must be a blockage of the intestine beyond that point. In babies especially, the concern was that the blockage might have been caused by a twist of the whole intestine (malrotation with volvulus), and this can be life-threatening.

I was watching the sunset through the windows of the ward when the ambulance crew arrived with our young patient. Up on the fourth floor we had a spectacular view over the city, and the sky was certainly putting on a show for us that night. The baby was oblivious to the commotion around him, laying fast asleep in his mother’s arms. A blanket bearing the darkest of green stains lay at the bottom of the trolley, leaving none of us in any doubt as to the urgency of this situation. Ms A was a model of calm compassion as she spoke to the baby’s parents and gently examined his tiny tummy, before a whirlwind of new activity saw fluids hung from a drip stand, an emergency bag pulled from a storeroom and a train of people pushing a cot (about as manoeuvrable as a supermarket trolley), setting off on a long walk to the x-ray department.

The scan involved a small amount of radio-opaque contrast dye being introduced via the baby’s nasogastric tube. The radiologist then took a series of x-rays to follow the dye into the stomach, out into the duodenum and on to the rest of the small intestine. In normal anatomy, we would expect to see the curve of the duodenum crossing from the right side to the left of the spine, then upwards to the same level as its exit from the stomach (called the pylorus). In this scan though, the contrast did not cross the spine, instead it ran down the right side and then spiralled in what looked like a black tornado. Exactly what we had been worried about: there was a twist.

Time was critical, now. A twist in the intestine cuts off the blood supply. If the blood supply is not restored within a matter of hours of the twist occurring, it may not be possible to salvage the affected intestine. If the whole intestine is lost, the baby cannot survive. We needed to get the baby to theatre, and fast.

After further conversations with parents, telephone calls to theatre, consent forms signed, Ms A called in the consultant and they took the baby for surgery. The plan was to untwist the volvulus and try to correct some of the anatomical anomaly that had led to this problem in an operation eponymously known as a Ladd’s procedure (after the American surgeon who had first described it in 1932).

Fully dark outside by now, once inside the theatre complex it was impossible to tell the difference between night and day. Dozens of staff attentively cared for this tiny patient and his parents. I witnessed the skill of the paediatric anaesthetist, using equipment small enough for a dolls house to take over the baby’s breathing. And then I saw the incredible moment when Ms A, having made her incision with such delicate precision, delivered loop after loop of deep purple bowel and, while warming it in saline-soaked gauze, untwisted the base, allowing blood to flow again. I saw the loops of intestine turn pink before my eyes. We call it ‘turning the clock back’: this procedure to untwist volved bowel. The phrase I think was introduced as a way to remind us that in almost all cases, an anticlockwise turn is needed to correct the anatomy, but of course it has the dual meaning of willing time itself to reverse. I think of it as the surgeon’s silent prayer that we got to it soon enough.

It seemed utterly miraculous to me that this cascade of events - the parents recognising the unusual vomiting, the doctors at the referring hospital arranging rapid transfer to a surgical centre, the transfer team arriving in time, the radiologist and their team performing the scan to make the diagnosis, all culminating in a surgeon’s hands physically untwisting the intestine, had prevented catastrophe: they had saved this baby’s life.

That night, my career path in paediatric surgery was determined. In the years that followed, I often joked with colleagues that I was so captivated by the miracle that I witnessed that I failed to take account of the fact that in choosing such an acute specialty I was condemning myself to a career of operating through the night forever. In all honesty, though, I never minded coming in at night for cases like this. They were literally what I was there for, and to be able to help was genuinely the greatest privilege, every time.

Twenty years later, in a different hospital, in a different city, I was the consultant called in to supervise a trainee performing a Ladd’s procedure for another baby with malrotation and volvulus. Thankfully, this baby too fared well. What coincidence though, that this would be my very last on call as a surgeon? That this particular case, this relatively uncommon procedure, would both start and end my career? Kismet? Perhaps. A perfect symmetry to bookend my surgical life. Walking out of the hospital as dawn was breaking, I looked up at the deep blue sky, tears of exhaustion, sadness and gratitude filling my eyes. I couldn’t have wished for a more fitting end.

I can only be what I can see

As much as I’m a woman of Science, (and how could I not be, having had the career I’ve had?) I am learning to take my place in the universe one step at a time, knowing that there will always be much beyond human comprehension.

One thing I am certain of, is the power of role models. The people who embody possibility, because they are living evidence of it. The people like Dr S, and Ms A, who showed me that women; that mothers, can be excellent doctors and surgeons and still have a happy home life. And the people who are showing me now that I can reinvent myself at the tender age of forty-something and build a career out of creativity. So, knowing that many of my readers may not be all that familiar with Substack as a platform for readers and writers, I’d like to conclude this article by introducing you all to just a few of the women who are inspiring me now (for if I listed them all, we’d be here all day). Please, if you have a few minutes, check out their work, they are wonderful.

My writing tutor, the talented author and generous teacher of writing and how to find joy in life -

My fellow former surgeon - soul sister - friend

The lovely Queen of Substack - go to person for everything you need to know about this platform and making the most of it -

The witchy and wonderful Mother Maker - who is teaching me how to find my muse and work with creativity to make magic -

My journalling coach and host of the most divine retreats -

Author of the most incredible poem I have ever seen performed on video -

For anyone worried about my son, please be reassured that he is no longer considering a career as a surgeon. He currently has his sights set on making his millions as a YouTube Minecraft expert. What a relief.

Louise x

If you feel inclined to support my writing, please would you click the heart button? This seemingly small action will help my work to reach more people. If you have any questions or comments, I’d love to hear from you. Alternatively, please do share this post or my homepage directly with your friends and family if they might be interested to read my work. Thanks so much.

I didn’t. I think I said something along the lines of ‘I’m sure if they really want to and work very hard then of course they can’, while willing the idea far from his mind, for I wouldn’t wish my experience on anyone, never mind this most precious child of mine.

I’d like to think that firstly, this question would never be asked today, but if it were, I would respond by calling out their misogyny rather than suggesting that I wouldn’t need to take time off if I had children. I was 18 years old. I had no idea if I would ever have children!

I’m joining this rather late, but want to say what a wonderful read, thank you. Ms A certainly recognised something in you, therefore asked if you wanted to stay and observe. A great many years ago, I switched from being a trained nurse to train as an audiologist. Yes,still in the NHS, but that change helped me personally. I wasn’t disabled then, but recognised that I was burnt out in my nursing role. The diverse knowledge gained in all careers always helps in subsequent ones, whatever they may be. All life experiences count. Wishing you the very best for the future.

Thanks for the mention lovely! What a beautiful read for me this afternoon. ✨